The rupee’s decline is not coming from the usual sources that people point to — not from high inflation, not from oil shocks, and not from any sudden deterioration in growth. The currency is weakening because the economic mechanisms that used to stabilise India’s external position have stopped working. And the roots of the problem lie inside the domestic economy, not outside it.

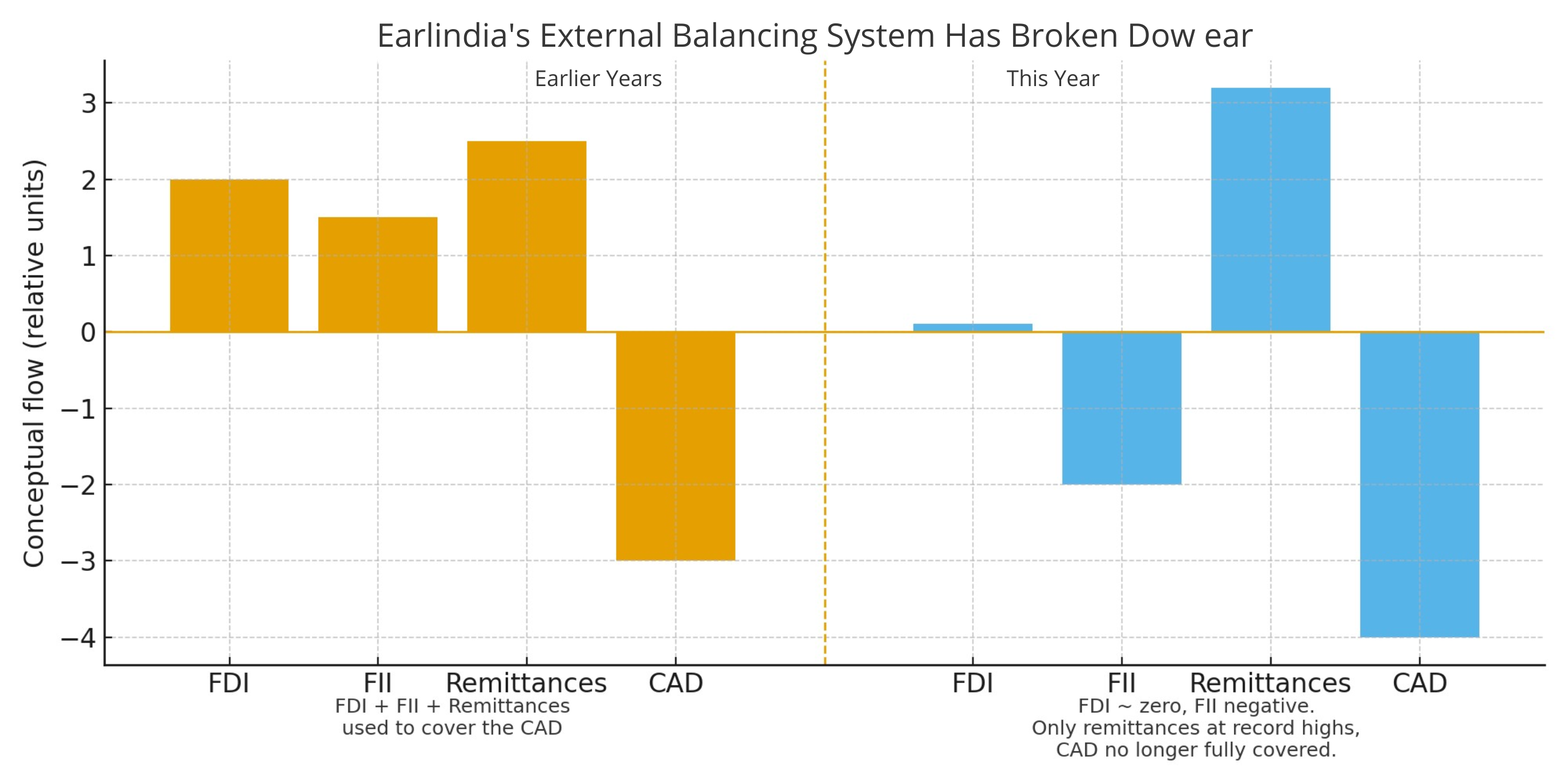

For over a decade, India comfortably ran a current account deficit because foreign capital reliably filled the gap. FDI used to be strong and steady, providing long-term dollars that offset India’s import bill. FII flows added an additional layer of support. When either FDI or FII was soft, the other usually stepped in. This balancing act kept the rupee broadly stable regardless of global volatility.

That system has now broken down. Net FDI has effectively fallen to zero, and FIIs are selling almost every day. This is the first time in many years that both long-term and short-term foreign flows have weakened simultaneously. With no external cushion left, even routine import demand is enough to push the rupee lower. The market is simply adjusting to a shortage of incoming dollars.

Why have foreign investors stepped back? The simple answer is that India’s nominal GDP growth is far too low, and low nominal growth is feeding directly into weak corporate profitability. Real GDP prints look strong, but companies operate in nominal terms. When inflation is close to zero, pricing power disappears, revenue growth stalls, and operating leverage evaporates. That is exactly what has happened over the past year: companies have struggled to grow topline, demand has softened in several sectors, and earnings momentum has slowed.

FIIs don’t react to headline GDP; they react to earnings. When profits slow while valuations remain expensive, outflows become mechanical. And once FIIs turn sellers, the rupee feels the pressure instantly.

The deeper cause of this weak nominal growth is twofold. First, the RBI misread inflation, expecting it to remain sticky when it was actually collapsing. Because of that mis-forecast, monetary policy stayed too tight for too long. Real interest rates rose sharply, credit conditions tightened, and demand lost steam. Near-zero inflation combined with high real rates is the worst possible mix for corporate revenues — and it is visible in the earnings slowdown FIIs are reacting to.

Second, the government’s investment strategy has been inconsistent. Centre-level capex is high, but state capex has fallen sharply, and private investment has not stepped in. The multiplier effect has been narrow, leaving consumption and broader demand weaker than expected. Without a strong nominal cycle, corporate profits have no runway, and foreign investors have no incentive to stay overweight.

Put together, the picture is simple: FDI has dried up, FIIs are exiting, nominal GDP is weak, corporate earnings are soft, and CAD is slipping. When all three external buffers weaken at the same time, the rupee has no choice but to adjust lower.

The currency is not in crisis — it is responding logically to a domestic flow imbalance. Until nominal GDP improves and earnings recover, the rupee will remain under pressure, regardless of global conditions.