Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are widely seen as simple, low-cost tools to invest in broad markets. But sometimes, ETFs trade at prices that are significantly higher than the actual value of their underlying assets. This mismatch happens when demand for a particular ETF far exceeds the supply of units available in the market. When that occurs, the price you pay on the exchange may be far more than what the ETF is truly worth.

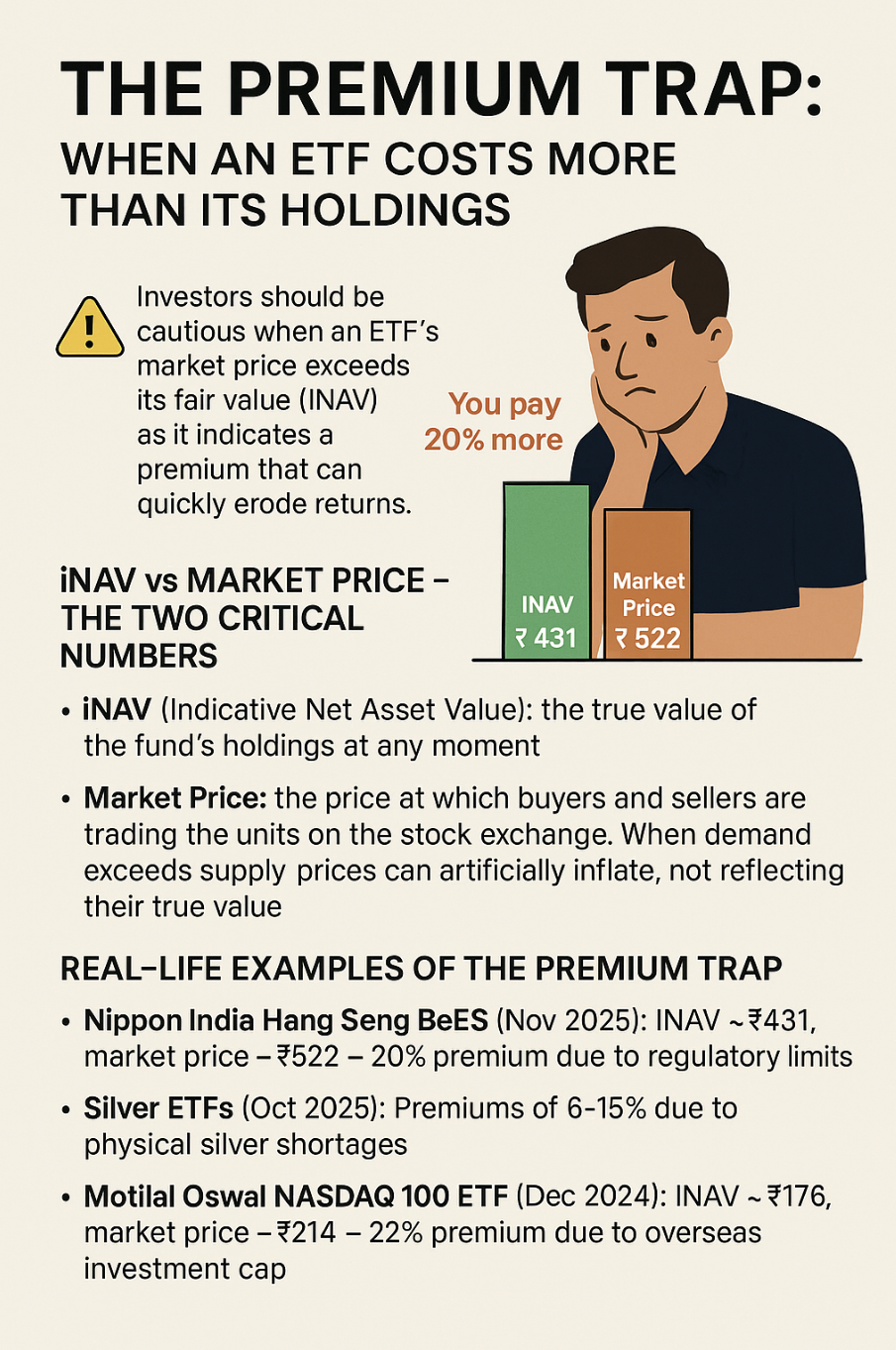

Every ETF unit has two important numbers. The first is the iNAV – the Indicative Net Asset Value. This is the real-time estimate of the value of the fund’s holdings, updated throughout the trading day. For example, in the case of the Nippon India Hang Seng BeES, the iNAV reflects the real-time value of the Hong Kong stocks that the fund holds. The second number is the Market Price – which is what you actually pay when buying the ETF on the exchange.

Ideally, the market price should stay close to the iNAV. But when fresh creation of ETF units is paused or limited, and demand from investors keeps rising, the market price can shoot above iNAV. That’s exactly what happened recently. In late November 2025, the Nippon India Hang Seng BeES had an iNAV of around ₹431, while it was trading on the stock exchange at ₹522. That means investors were paying roughly 20% more than the actual value of the ETF’s holdings. This happened because SEBI’s foreign investment limit had been reached, stopping the creation of new units. If and when these restrictions are eventually lifted, the AMC will be able to issue new units at the iNAV. As a result, the premium will disappear—meaning the market price could drop even if the Hang Seng index itself does not. Investors who paid a premium will face losses without any movement in the underlying index.

This isn’t the only example. In October 2025, during a sharp rally in silver prices, several silver ETFs in India traded at noticeable premiums. The Nippon India Silver ETF, for instance, was trading at ₹156 while its iNAV was around ₹148.3 – a 5.5% difference. Other silver ETFs, such as those from HDFC and Tata, also saw premiums between 10% and 15%. This happened because silver ETFs in India must hold physical silver to back every unit they issue. So when investor demand surged suddenly, the fund houses couldn’t immediately create new units until they could acquire and store additional silver. Global supply delays, high prices, and import restrictions made this process slower and more expensive. As a result, existing ETF units became scarce and started trading at inflated prices on the exchange.

A similar case was seen in early 2022 with the Motilal Oswal Nasdaq 100 ETF. At the time, it was trading close to ₹99 when its iNAV was about ₹87 – showing a premium of nearly 14%. Again, this was due to restrictions on overseas investments that froze new unit creation even as investors rushed to gain exposure to U.S. tech stocks. The premium eventually vanished as market flows stabilized, but the initial distortion exposed many investors.

To avoid falling into this premium trap, investors must always check the latest iNAV before buying an ETF. If the market price is more than 1–2% higher than the iNAV, it’s best to wait. Buying into a 10% or 20% premium exposes you to an immediate loss when the gap closes. ETFs work best when you buy them close to their true value.