A disturbing pattern is emerging in India’s capital markets. Mutual funds that once prided themselves on valuation discipline are now acting as exit vehicles for venture capitalists and promoters at sky-high prices. The case of Lenskart’s IPO illustrates this perfectly.

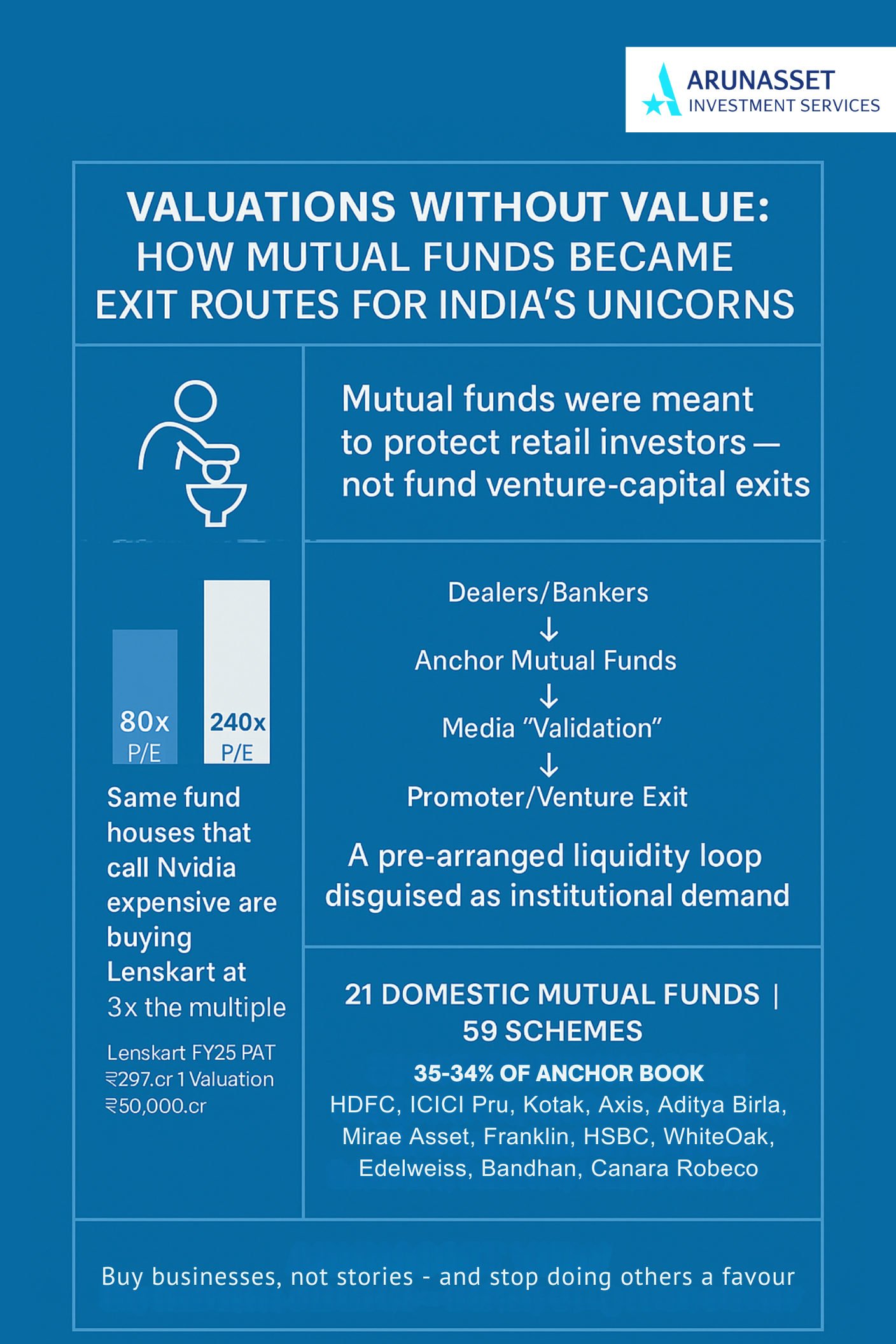

The same fund managers who call Nvidia a bubble at 80× earnings have happily written cheques for a domestic retailer at over 240× P/E. The irony is obvious: Nvidia sits on decades of proprietary technology, patents, and ecosystem lock-in — a true moat. Lenskart, by contrast, has none. It sells imported frames and lenses through franchise stores and a website any competitor can replicate. There’s no technological edge, no IP, no supply-chain exclusivity — just brand marketing and distribution muscle powered by abundant capital. Yet it’s being valued richer than some of the world’s most defensible businesses.

The justification is wrapped in buzzwords — “India consumption,” “digital retail,” “global expansion” — but the mechanics tell a different story. Dealers running the issue secure early anchor commitments from fund houses with whom they share long-standing relationships. Once a few marquee MFs sign on, that inflated valuation becomes gospel. The media calls it institutional validation; in reality, it’s a pre-arranged liquidity window that allows early investors to exit at a premium.

According to the IPO’s anchor allocation filing, 21 domestic mutual funds across 59 schemes participated — together taking over a third (35.34%) of the anchor book. The list includes HDFC Mutual Fund, ICICI Prudential Mutual Fund, Kotak Mutual Fund, Axis Mutual Fund, Aditya Birla Sun Life, Mirae Asset, Franklin India, HSBC, WhiteOak Capital, Edelweiss, Bandhan, and Canara Robeco, among others. These are India’s most trusted fund houses — and yet they’re underwriting valuations that even Silicon Valley VCs would hesitate to justify.

Look deeper, and the proceeds from many of these issues barely fund business expansion. They’re mostly secondary offers — cashing out venture capitalists and promoters. The risk is quietly passed on to retail investors through mutual-fund NAVs. A small allocation of about 0.3% in a “growth” or “consumption” fund may look harmless, but collectively it represents thousands of crores of retail savings underwriting private-equity exits.

The real problem is incentive distortion. Fund managers today compete less on long-term returns and more on asset gathering and headline participation. Saying “we owned Lenskart pre-IPO” looks good in presentations, even if the math doesn’t hold. It’s an easy way to appear visionary without taking real analytical risk. This isn’t capital allocation — it’s asset marketing dressed up as conviction.

When mutual funds start paying venture-style prices for mature, low-moat businesses, they stop serving investors and start serving the exit needs of others. Retail capital deserves better — clear disclosure, genuine price discovery, and a return to first principles: buy businesses, not stories, and stop doing others a favour at the expense of your investors.